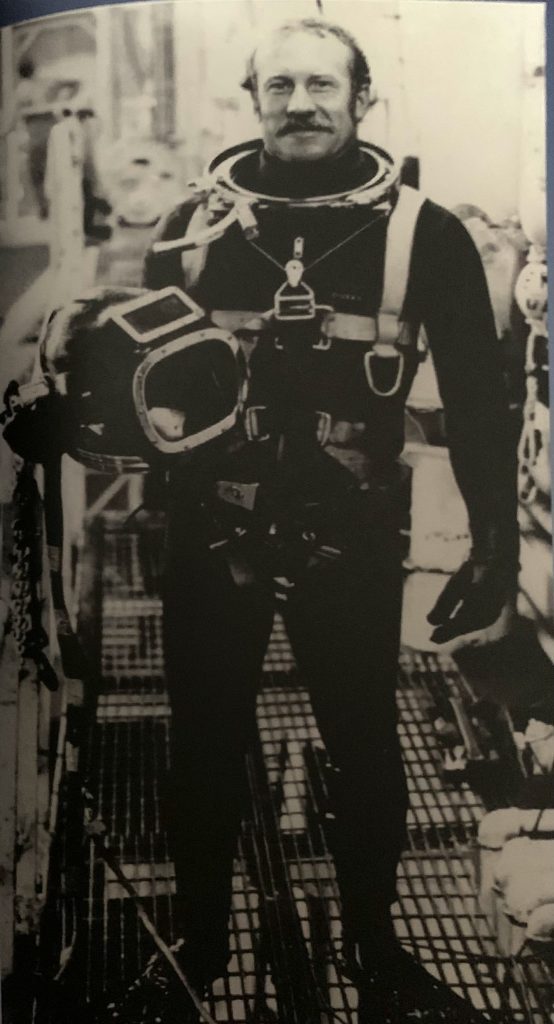

Lloyd Sorenson has experienced a lot, whether way above or way below the sea

Lloyd Sorensen has led, by all measure, an incredibly exciting and adventurous life — in the air, on land, and on and under the sea.

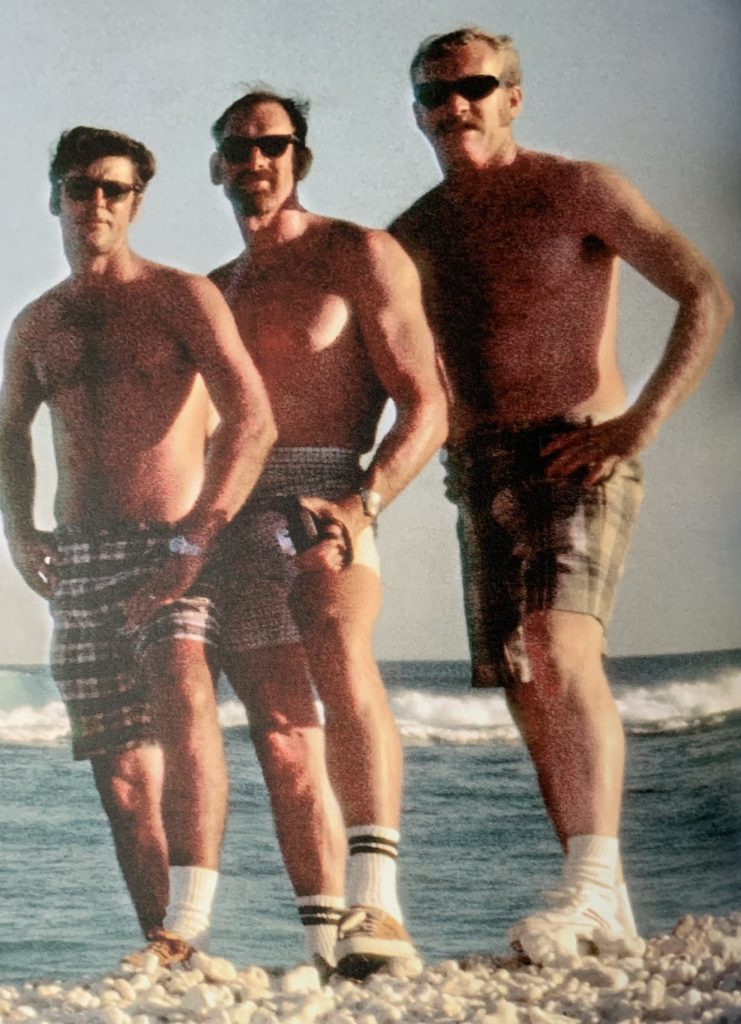

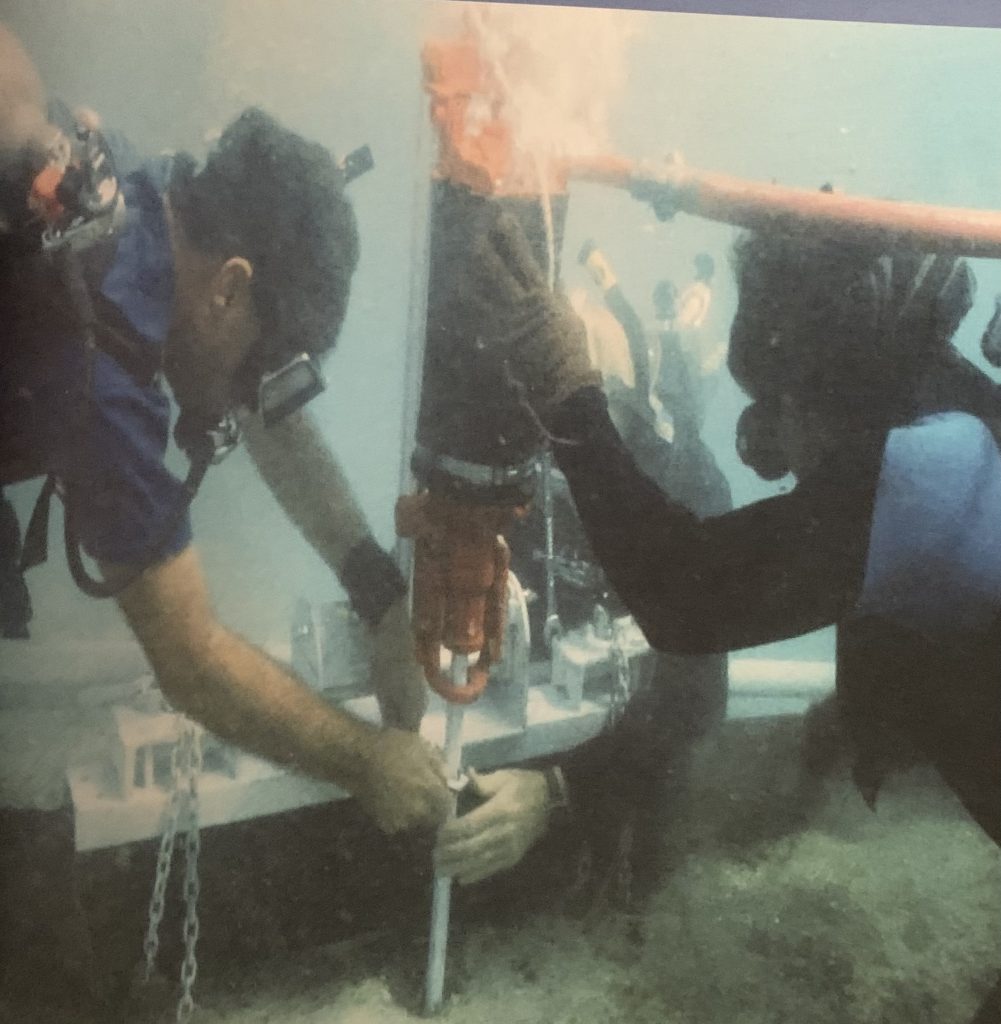

A 445-page book titled “Three Oceaneers” documents 25 years of his work and adventures as an underwater diver along with his two lifelong best friends, Dave Schiefen and Richard Hegeman. One of Sorensen’s many adventures included working as a diver on the “top-secret” Project Jennifer, the codename applied to the CIA project that salvaged part of a sunken Soviet submarine in 1974. The Soviet ballistic missile submarine sank off the coast of Hawaii on April 11, 1968. In July 1974, salvage operations conducted from the Hughes Glomar Explorer recovered the forward 38 feet of the submarine. The recovered section included two nuclear-tipped torpedoes, various cipher/code equipment and eight dead crewmen.

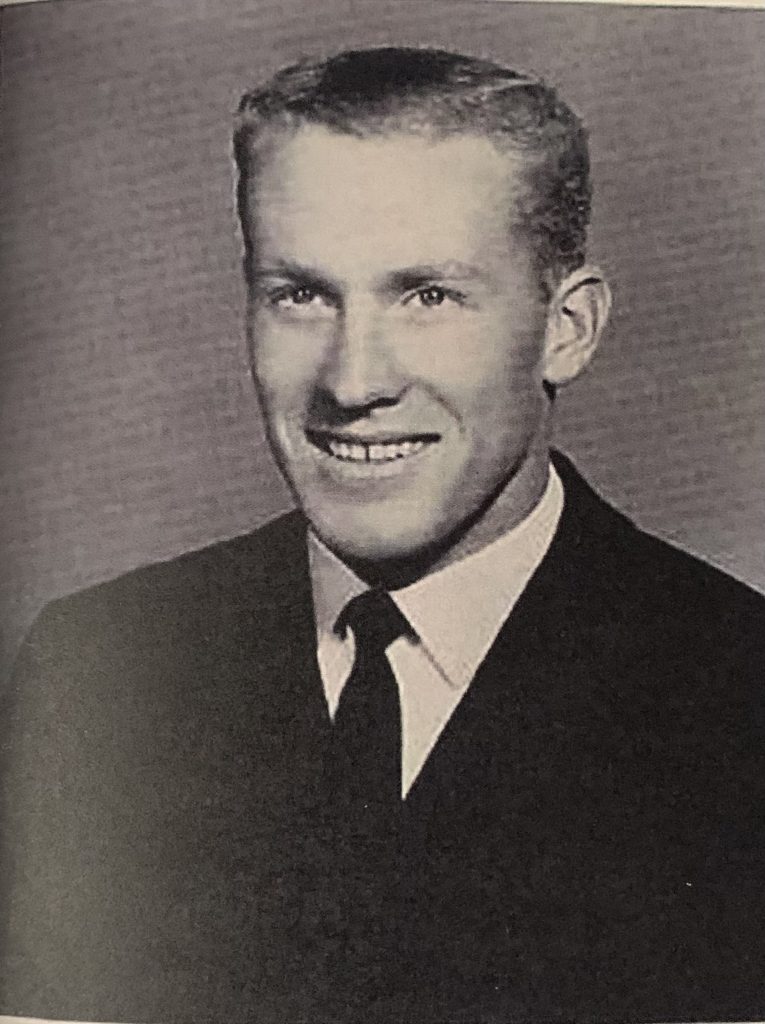

Sorensen was born in 1938 in Santa Cruz. His father worked in highway construction all over California, so the family was constantly moving. By age 3, his family had moved 10 times. His mother insisted on living in one place and owning a home. His father found a house in Oakland Hills and with a $10 down payment, it was purchased.

He graduated from high school in Oakland in 1956 and attended junior college for a short time, working part-time at Continental Can Company, making beer cans to earn money to continue his education. One of his high school friends went on to attend the California Maritime Academy (CMA) and Sorensen became interested in the CMA, soon applied and was accepted. The CMA was a three-year, 24/7, quasi-military program, which included ocean deployment on a ship converted for the purpose of teaching and included classrooms. Sorensen maintained records of his ocean deployments while at CMA. As a student, he traveled to numerous ports in the United States and foreign countries and logged in more than 25,000 miles.

Sorenson graduated from the CMA in 1960 with a Bachelor of Science degree in marine engineering. Before receiving his degree, he was required to pass the U.S. Coast Guard Marine Engineers exam, which he did, earning him a third assistant license for steam or motor vessels of any horsepower. Then he became a member of the Marine Engineers Union. He soon moved to New York City to live with a friend, and soon went to the local union hall to register for upcoming jobs and to his astonishment, a position was open on a freighter leaving that night! Sorensen was on his way to South America.

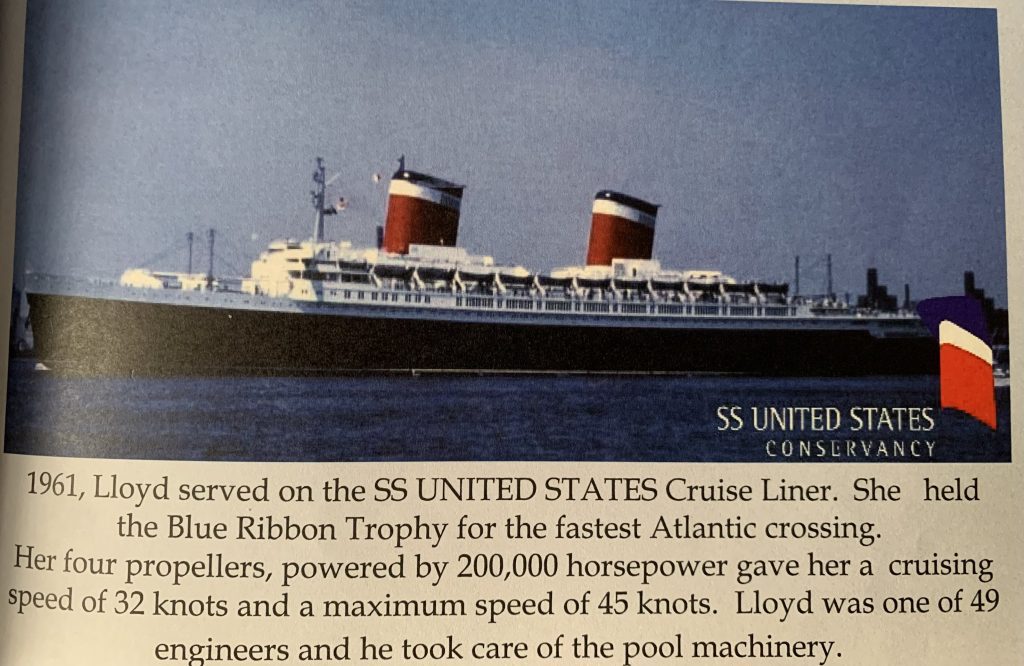

Upon his return from South America, he served on the SS United States Cruise Liner and traveled to Europe from March 28, 1961 to April 12, 1961.

“The SS United States was the most luxurious, fastest, and largest ship at the time. It took only five days to cross the Atlantic from New York to France,” said Sorensen. “But that was just one of many I worked on.”

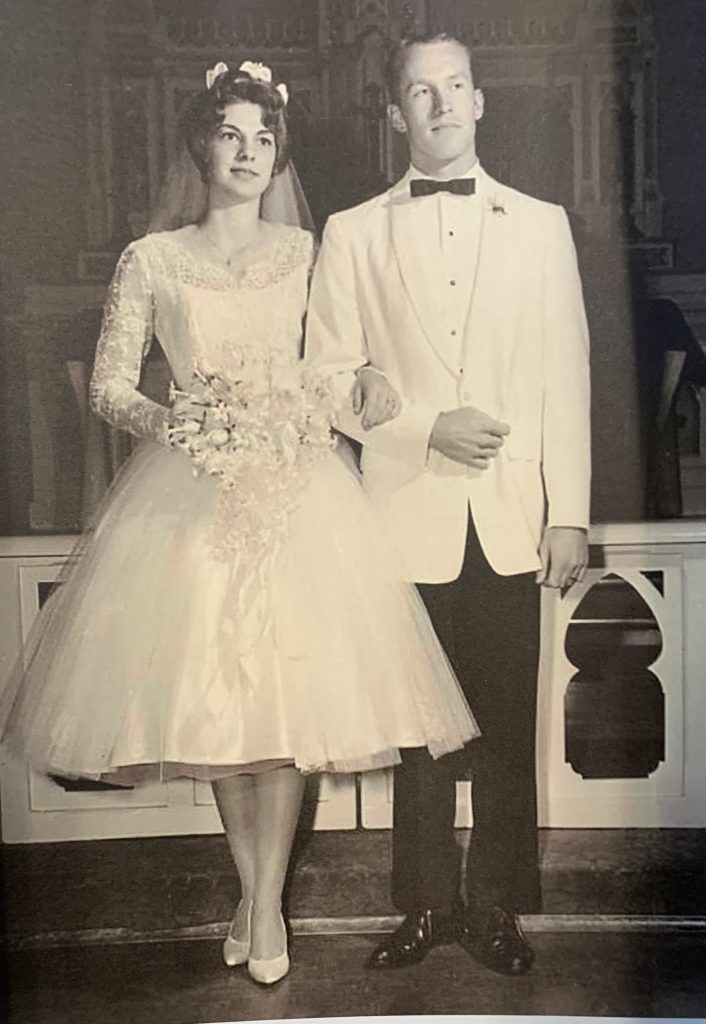

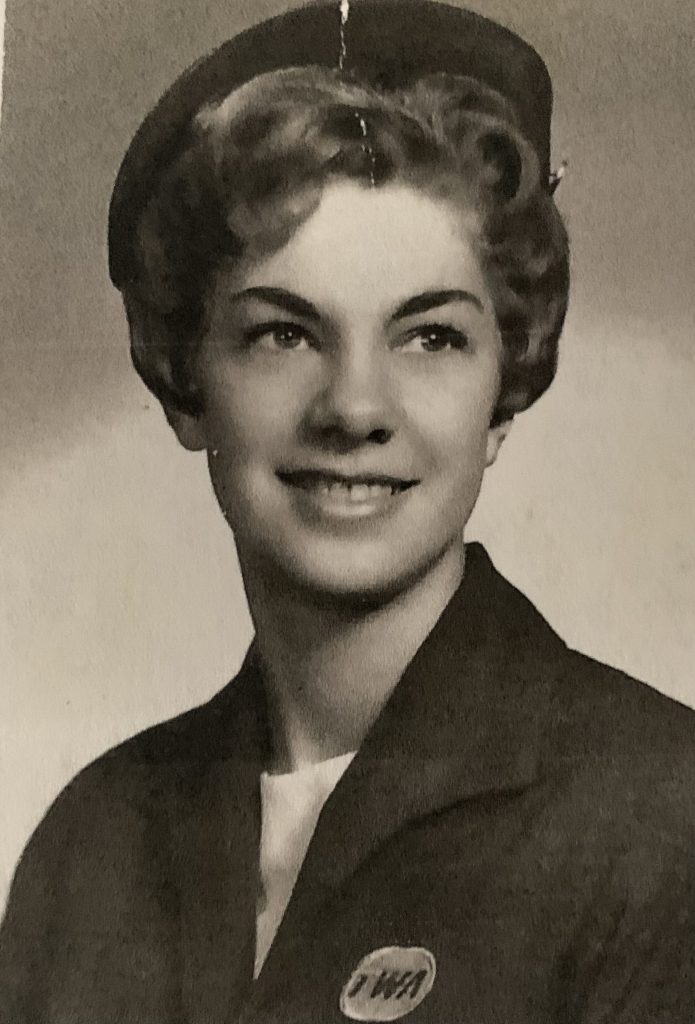

Sorensen continued to ship out from New York City on several merchant ships to South America through August 1961. He happened to be in Santa Barbara for Old Days and was introduced to Sharon Anne Nelson, a TWA flight attendant out of Los Angeles who lived in Santa Monica. Lloyd and Sharon soon became a couple and were married in Portland, Oregon, her hometown, six months later, on Feb. 17, 1962. After their wedding, they moved to Oakland, California, and Sharon was transferred from Los Angeles. She flew domestic flights out of San Francisco, until air turbulence during a flight caused her to take a rough fall and a subsequent examination revealed she was three months pregnant. No more flying; she was grounded.

They have now been married for 62 years. They have two children: a son, Stephen Lloyd and a daughter, Kristen Anne.

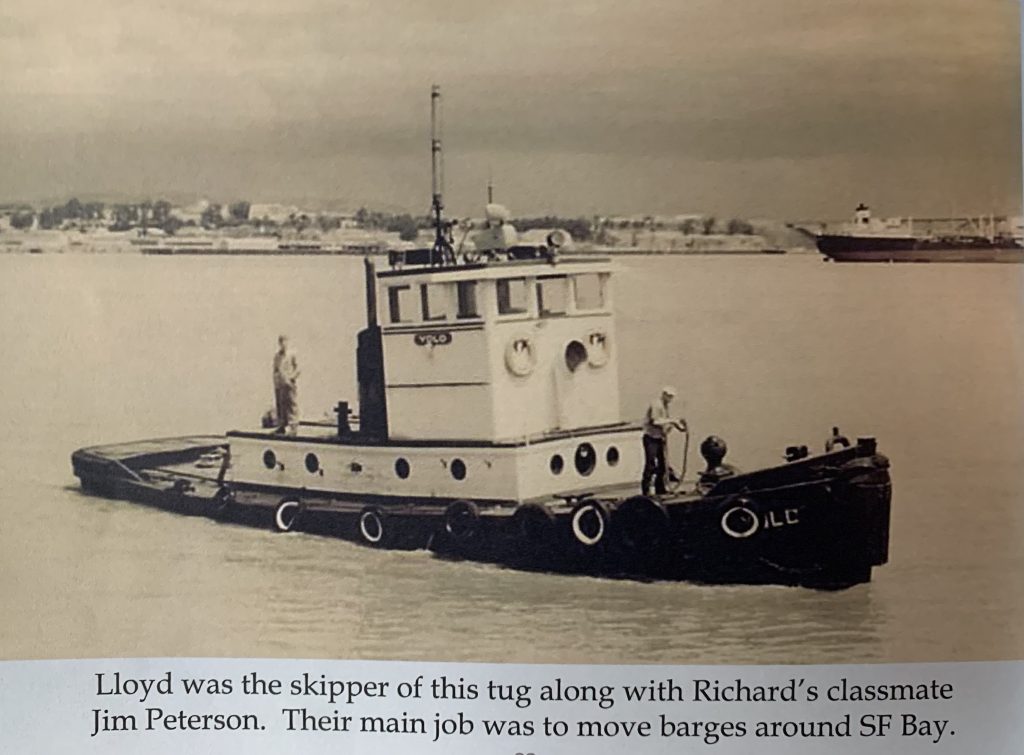

From 1962 to 1965, the Sorensens lived in Oakland. He worked as a tugboat skipper moving barges around the San Francisco Bay. He left the operations after his tugboat sank when it was hit by a ship. Fortunately, he was not on the tugboat, but on a barge being moved by the tugboat.

“When he worked on the tugboat, he was gone two days and nights a week and was then home for three days,” said Sharon.

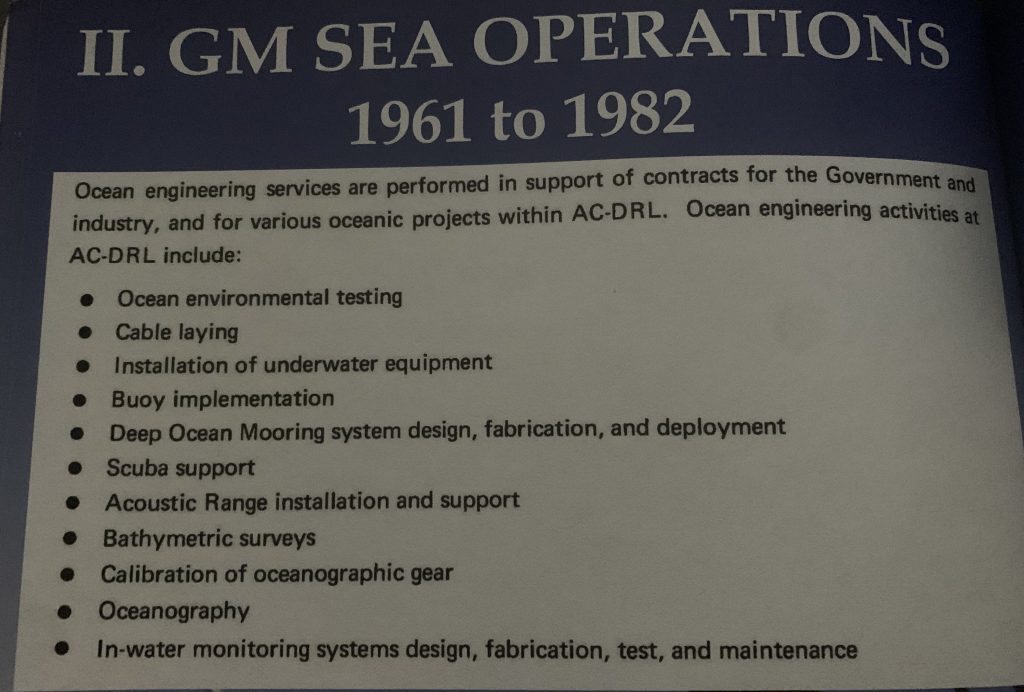

By 1965, Hegeman and Schiefen, Sorensen’s classmates and friends from the CMA, were already working for General Motors Sea Operations. He joined them at General Motors in May 1965 and moved his family to Goleta. Sorensen, Schiefen, and Hegeman all started as engineers aboard a research vessel and were also trained as divers to support underwater work. They assumed roles as project engineers and program managers. The GM engineering services were performed in support of government projects which were highly classified in nature.

“General Motors had a sea operations division: The Santa Cruz Acoustic Range Facility (SCARF), a research vessel called the Swan. It was a mine sweeper that was converted into a research vessel,” Sorenson said. “Dave was the first one to sign on, then Dick came on second and I came on third, as engineers on the ship. Part of it involved installing underwater sounding equipment for the Navy, which they needed. A system on Santa Cruz Island put an instrument on the bottom of subs and ships for noise trials. I got a Rolex watch after 1,000 dives.”

An article about SCARF in a Santa Barbara Marine Museum newsletter explained that bottom-mounted sensor arrays in 4,000 feet of water tracked submarine and surface ship movements. As submarines transited by the vertical string of hydrophones, noise measurement information was gathered. Underwater cables transmitted the information to the shore station, and an Underwater Communications System (UQC) allowed the shore station (located on the south side of Santa Cruz Island) to communicate with the submarines. This monitoring was vital in recognizing submarines’ vulnerabilities and recommending corrective actions to reduce radiated noise. The entire shore facility and its in-water system were removed in 1990, and the area was returned to its natural state.

“But one of the most interesting jobs I had was on the Hughes Glomar Explorer, a top-secret CIA project that salvaged part of a sunken Soviet diesel-electric submarine K-129 in 1974. The cover story was we were mining for magnesium nodules,” Sorensen explained. “When we pulled it up there were bodies on board, so we buried them at sea. There were also three warheads on the sub, and when it was lifted out of the water the left part of the sub broke and fell back into the sea. The recovery machine was called the Clementine.”

Sorenson, fortunately, was able to avoid that kind of catastrophe.

“We had a really strict diving program with General Motors, so no one was ever injured in our group,” continued Sorensen. “They even had a doctor, Dr. Geer, who made sure we were always in good health. The divers covered for each other when the sharks appeared. One guy would do the work and the other two divers would keep the sharks away using Billy-clubs.”

And all of it was done top-secret.

“There have been a lot of books and stories written about that job, but that was long after the job was over. The CIA kept it under wraps for years, but then the story finally came out,” he said.

Sharon remembers that time well.

“One of the benefits when he was diving around Santa Cruz Island in his spare time was the lobsters. They would dive for lobsters, abalone, and all kinds of fish. We were eating well when we hadn’t any beef on hand,” Sharon recalled.

“I’ve been around the world putting in sound systems – 166 ports around the world,” her husband stated.

“I went on some of the trips with him, but a lot of the assignments were secretive, so I just stayed home with the kids and didn’t ask questions,” continued Sharon. “He was gone six months out of the year. It took a little adjustment on my part when he came home, as you can imagine.”

In 1982, Sorensen and several members of the underwater team left General Motors and formed their own company. They continued to perform sensitive operations laying underwater fiber optic cable throughout the world.

“When General Motors decided to cancel their program, 14 of us started MariPro Corp. and took on one of the contracts with the Navy, who was our basic customer,” Sorensen said.

MariPro’s offices were located in Santa Barbara on the airport property in a building outside of the airport. In 1968, Sorensen commented to his wife that he was going to learn how to fly, something he had wanted to do since he was a boy. He did just that and then bought a 1948 Cessna 140, which he flew from the Santa Ynez Airport to Santa Barbara.

“The timing was exactly the same as driving, by the time you take the plane out of the hangar and eventually get it in the air,” commented Sorensen. “But I did that for years. I logged 900 trips to work alone.”

During his career, Sorensen logged more than 1,500 underwater working dives in support of projects around the world, and numerous recreational dives. He retired from MariPro in 2010.

“He remained working for an extra 10 years because he enjoyed the work and working with his friends so much,” said Sharon. “The three of them are the best of friends to this day. They got to travel around the world together; they did work for the United Nations, and installed eight sounding systems around the world, initially to detect nuclear testing. They worked on Amchitka Island in the Aleutian Chain of Islands in southwest Alaska, a part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. They spent their lives together. They’ve been friends since school.”

“It was cold, diving off Amchitka,” Sorensen recalled. “You had to dive in dry suits, but they don’t look anything like they do now.”

Sorensen reflected on his life.

“I’ve lived a life well spent. But I never learned to cook because I’ve always had someone to cook for me,” said Sorensen, smiling. “Kidding aside, I’ve been very blessed. I have been married for over 60 years to my beautiful wife, have two wonderful children, a son and daughter, no grandchildren yet, just grand dogs, and I’ve traveled the world.

“When I was in the Merchant Marines one day it occurred to me that I was enjoying the fruits of my labor while I was young, seeing that most of the passengers on these freighters were old people. So, I said to myself, ‘That’s not right — you should be able to travel when you are young.’ I have been very fortunate to be able to see the world during my whole working life.”

When asked what his favorite place was that he’d visited, he said, “I think my favorite place in the world is Kauai, Hawaii — but there have been so many beautiful places I’ve seen in my life, it’s hard to choose just one.”

Note: Eusebio Benavidez contributed information for this article.