By Pamela Dozois

Contributing Writer

One rarely thinks about how all the products we have at our disposal make it to our shores from distant countries. How do these huge ships, filled with valuable cargo, navigate into our ports to be unloaded?

Captain Jackson Pearson thought of nothing else throughout his career as a pilot in the Port of Los Angeles — eventually becoming its chief pilot — in a career that lasted for 30 years.

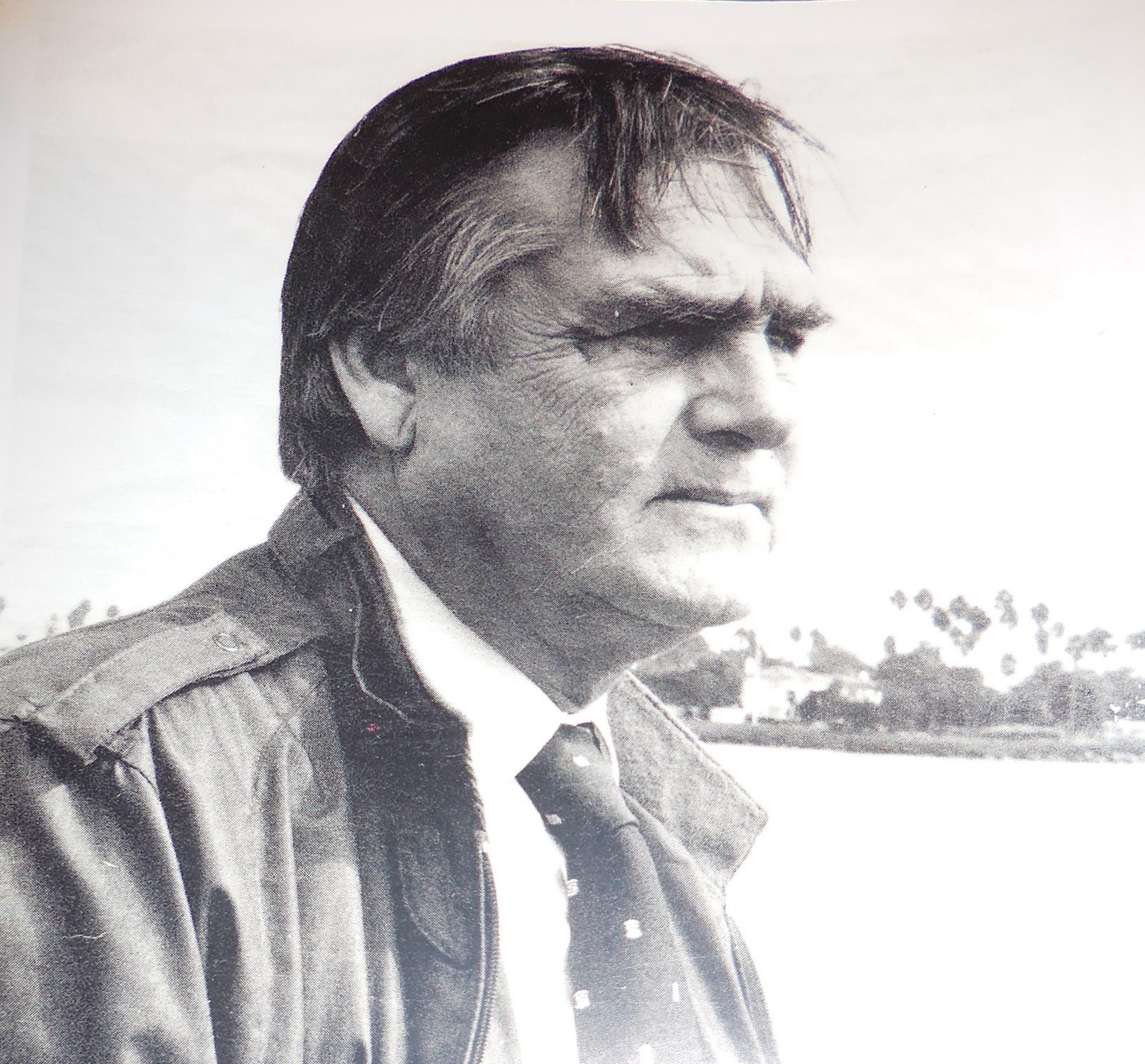

Captain Jackson Pearson and his wife Edie are shown at their home in Santa Ynez.

“The average ship’s captain doesn’t know all the nuances of docking his ship in port,” said Pearson, who lives in Santa Ynez with his wife, Edie. “In a port, he depends on a pilot who has a license to navigate the vessels in and out of the harbor, because the pilot is the one with all the local knowledge and training to safely bring the ships in and out of port.”

Pearson explained that ships remain three miles outside of port and a pilot boat is sent out to meet the ship. A Jacob’s ladder, a rope ladder, drops from the deck to the pilot boat below. The pilot then ascends and, once on board, takes command of the ship, with the permission of its captain, and brings the vessel into port.

“Four thousand ships a year come into the Port of Los Angeles,” said Pearson. “There are only 15 licensed pilots that serve the Port of Los Angeles. The job is very rare and specialized in the maritime industry.”

Born in 1927 in San Pedro, Pearson was considered a “bad boy” in his youth, getting into trouble with the law. His probation officer told him to quit stealing cars and join the Merchant Marines. He did, leaving school before he graduated.

After serving on the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific training ship called the Invader, out of San Francisco, he found employment as a deckhand for the Tidewater Oil Company. The first ship was the Merchios H. Whittier, which sailed along the coast and to Honolulu. Over the next two years he worked on several other tankers and tug boats, learning to become an able-bodied seaman, as were his father and grandfather before him.

“My grandfather, Arne Petersen, had been a pilot in New York Harbor, holding a master’s and pilot’s license in New York in 1903, and my father was in the Navy during World War II before becoming a longshoreman,” he said.

The first large ship Pearson piloted into the Port of Los Angeles in May 1960 was the Torrey Canyon, a 900-foot oil tanker.

Pearson said he worked very hard learning the skills needed to be a seaman, from the deck up, studying while on board the various ships on which he worked. In 1943, his first trip to sea was on a tanker owned by the Associated Oil Co., later Getty Oil Co. In 1944 he was hired by the Wilmington Transportation Company as a deckhand and by May 1945 he was promoted to captain of the tug Vivo.

Then duty called. From 1945 to 1946 he served in the U.S. Army, stationed in Seattle.

Following his service, Pearson worked as a commercial fisherman and then returned to the Wilmington Transportation Company in 1948, alternating between captain and deckhand. In 1948 he apprenticed as ship pilot and by 1950, after receiving his pilot’s certificate, was promoted to ship pilot along with tug captain’s duties, working for them for 16 years.

In April 1960 Pearson became a city of Los Angeles port pilot. He graduated third in his class and was hired immediately to fill in as a temporary pilot for 60 days. The first large ship he piloted in May 1960 was the Torrey Canyon, a 900-foot oil tanker. That temporary position turned into a full-time job and he worked at the Port of Los Angeles for the rest of his career, becoming the chief port pilot in 1983 until he retired in 1990. Pearson was the youngest pilot, at age 32, to work as a pilot in the Port of Los Angeles.

“It took quite a bit of devotion to get through the learning process … especially if you didn’t go to one of the “new” schools like the USMMA (U.S. Merchant Marine Academy) to study. I studied at the Merchant Marine School, Crawford Nautical School, the “old” school, in San Pedro to learn navigation and received a mate, master’s, and pilot’s certificates. I am a captain and pilot in the U.S. Merchant Marines,” he said proudly.

“I had a master’s license before I had a high school diploma,” he joked. “I finally obtained a high school equivalency diploma, then went to Harbor College, at age 44, and obtained an associate of arts degree. I then graduated from Cal State Dominguez Hills and received a degree in anthropology. That was just before I was made chief port pilot.”

In 1984, he received the Amicus Collegii Award for outstanding alumnus of Harbor College.

“Of all the awards I have received, and there have been many, this one was the most prestigious and the best award of all,” he said.

During his illustrious career, Pearson has brought many enormous ships into port without any significant incidents. Included were the 1,092-foot tanker the Williamsburg and the HMS Bounty. In 1975, Pearson brought the Cunard Lines’ Queen Elizabeth II into the port of San Pedro for the first time.

“She was easy to handle, despite being the largest passenger ship,” said Pearson. “I brought her in and I took her out.”

Pearson also acted in a 1955-57 television series called “Waterfront” with Preston Foster.

“I played his son, but in real life I was the captain of the tug boat the Cheryl Ann, which was the television name of the tug,” said Pearson.

In retirement he was the curator for the Los Angeles Maritime Museum for nine years.

Pearson and his wife Edie began taking trips around the world in 1983. He was a member of the International Pilots Association, which held conventions every five years in various locations worldwide.

The couple were married in 1972. Pearson has two children from a previous marriage, William Pearson and Heidi Jordan. Edie has four children from a previous marriage, Mark, Steve, John, and Monica (Becker) Cordero. The couple celebrate each wedding anniversary in Carmel, where they spent their honeymoon and haven’t missed a year since.

“We have had a wonderful and adventurous life together. It has and continues to be fun and exciting,” Edie said.

When Pearson retired as LA’s chief pilot, he received a congratulatory letter from a high school friend, Nicholas Dillan, the other “bad boy. Dillan became the principal of Lodi Unified School District.

“Not bad for a couple of ‘bad boys’ from San Pedro,” Pearson said. “We turned out just fine, I’d say.”

His last, most endearing reward came in the form of a letter from a fellow pilot in Long Beach. It read, “It is men like you that do honor to the seafaring profession and make the waterfront a fine place to work.”