By Raiza Giorgi

There were no ejection seats in the planes James Kunkle flew during World War II.

A pilot like Kunkle who was lucky enough to survive being hit by enemy fire would have to climb out of his plane as it plunged to Earth, avoid being hit by the plane, and then open his parachute.

“I talk to these young pilots who just press a button nowadays, and they can’t imagine having to climb out of their planes,” Kunkle said.

Kunkle will be honored as the grand marshal for the Fourth of July Parade on Independence Day in Solvang Tuesday.

First Lt. James Kunkle is seen at the A-78 airfield in Florennes, Belgium during World War II.

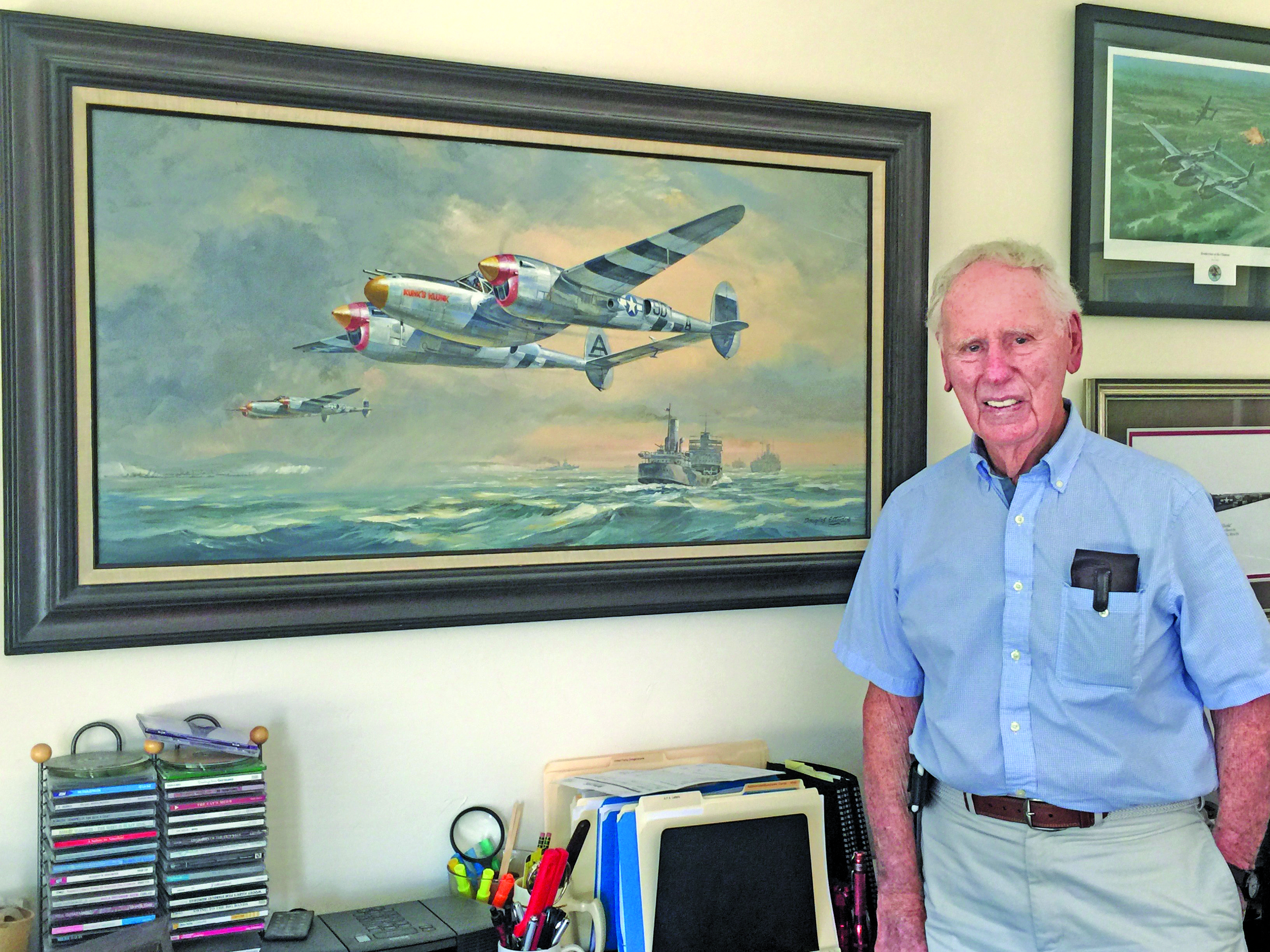

The decorated combat veteran recently talked about his journey to becoming a pilot and how being around airplanes has shaped his entire life.

The theme of the annual parade, sponsored by the Solvang Rotary Club, will be “American Heroes”. Kunkle is just that, although he is very modest as he talks about his time in the war, saying that anyone in his position would do the same thing.

For as long as Kunkle can remember of his more than 90 years, he has always loved airplanes and wanted to be a fighter pilot.

“Planes were a remarkable thing when I was a young kid. I remember being awed when we were listening to the tales of Charles Lindberg’s flight across the Atlantic Ocean in that rickety plane of his. The days of flying were newer then, and people would dress up to be on an airplane,” Kunkle said.

He did meet Lindberg once and was able to speak with him for a few moments. He recalls Lindberg as a nice man and feels honored to have met his hero.

Kunkle and his mother moved to West Hollywood from Pennsylvania when he was 9 years old, after his father died.

When he was a junior at Beverly Hills High School, Europe became engaged in the war.

“I knew we would be getting involved, and I thought if I wanted to fly I better get some experience. I joined the National Guard and worked at the airport.”

He then got a job in April 1941 working for North American Aviation, building planes. He eventually went to Lockheed where he was an inspector on P-38s and spent as much time flying as he could.

“It cost $6 an hour to fly then, which was expensive since most people made 50 cents or a little more an hour,” he recalled.

Kunkle said he was riding his horse in Griffith Park when a friend of his, musician Johnny Johnson, found him and told him about the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

“I thought ‘Gosh, I better get to the recruiting office and sign up,’” Kunkle recalled.

After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government lowered the age and education limits for enlisting, because they needed more people to sign up.

“I got my dream fulfilled to become a fighter pilot and was sent to London. I respect my fellow aviators from England and Canada and South Africa that came to fight,” Kunkle said.

He was assigned to the 9th Air Force, which was responsible for supporting the ground troops after D-Day. They were also in charge of attacking anything that moved, as they wanted to cut off supplies to enemy forces.

On Sept. 15, 1944 we was shot down near Aachen, Germany, while protecting fellow pilots.

He wasn’t able to communicate with his command and broke from formation to attack the enemy alone. He was able to hit two enemy aircraft before his plane was shot down. He suffered multiple burns as he climbed out, but he was able to open his parachute and land near some American infantry.

World War II veteran and Santa Ynez Valley resident James Kunkle met then-President Barack Obama at D-Day ceremonies in Normandy in June 2009.

Kunkle was honored with the Distinguished Service Cross and honored by then-President Obama and French President Sarkozy in a D-Day commemoration ceremony in June 2009.

After Kunkle was shot down, treated for his burns and released from the hospital, he was flown to Portland, Ore., where he helped to test the latest flight equipment and was preparing to go back to the Pacific for the invasion of Japan when the atomic bomb was dropped, which ended the war.

“Some of the unsung heroes of the war were the WASPS (Women Airforce Service Pilots). I knew most of them and those that flew knew them, but they weren’t recognized at the time they should have been,” Kunkle said.

He also had a great friendship with Barbara Erickson London, a pioneering woman pilot who helped pave the way for other women aviators.

“Those gals were amazing and were integral to the effort,” he said.

Kunkle’s friend Barbara Erickson London was a heroic aviator who helped pave the way for the women pilots who played a pivotal role in World War II.

Kunkle helped teach London’s daughter to fly, and her granddaughter flies airplanes in the Santa Barbara area.

“When the war ended I spent more time in the military, flying some of our first jets, and I wanted to stay on active duty. It was amazing to be able to fly the P84 Thunder Jet, and when I finally got out of the military in 1948 I went back to the family business of selling shelf paper,” Kunkle said.

The shelf paper business was very successful; their company sold paper that was treated with a safe insecticide, which killed bugs on contact.

“The South had a real bug infestation problem in those days, so our paper was super popular. It afforded me to get out of the business and get back into aviation, developing and building hangars,” he said.

Kunkle and his first wife moved to the Santa Ynez Valley in the 1970s because they loved the Santa Ynez Airport and its potential. After her death, Kunkle met his wife Ruth. They say their relationship started with love at first sight. She worked at an airport in Colorado where Kunkle was developing hangars.

“We just love flying together. This airport is our second home. What better way to spend our retirement than flying at the best little airport?” Ruth said.