Chris Bratcher hopes Cal Poly students can provide him a high-tech hand

By Drew Esnard

Chris Bratcher hasn’t allowed the loss of his right hand to slow his roll through life. He’s taken on the challenges resulting from a traumatic winemaking accident with a sense of curiosity and enthusiasm.

Using a 3D scan of Bratcher’s left arm and hand along with precise measurements and a 3D printer, the QL+ team of students created a socket for an artificial right hand.

And, when an unexpected offer arose from a group of Cal Poly engineering students to devise a custom prosthetic, he greeted the opportunity with the same spirit.

Wine industry folk, and perhaps many other locals, will remember the story—a grape de-stemmer severed Bratcher’s hand just above the wrist while he was making wine for his Bratcher Winery label in September 2014.

The accident “certainly created physically challenging issues for me, but my life isn’t any harder than it was. It’s not any less full. I’ve always been somebody who loves challenges, and in that way this has been an intense challenge. I find that interesting,” Bratcher said.

The world of prosthetics has proved to be an interesting challenge in and of itself. Bratcher is currently using a conventional, body-powered hook prosthesis. The experience has been rather dismal as the straps are difficult to secure and the different sockets have presented Goldilocks-like problems. They’re meant to fit snugly yet comfortably over his residual limb, but the sub-par fit of each socket causes great discomfort.

Additionally, Bratcher has been experiencing significant pain from the overuse of his left arm that has resulted in tendinitis. Cortisone shots have been effective in relieving the pain temporarily, but he had to stop the treatment, as long-term use would likely cause irreversible damage to the tissue.

The artificial hand will be controlled with sensitive electrodes that respond to the natural movements of muscles.

Not surprisingly, Bratcher became a bit nervous over the prospect of becoming more dependent on others for basic tasks, consistent denials from his health insurance company for a better prosthesis, and the progressively debilitating pain in his left arm. Nervous, but not discouraged.

“I’m determined to get back. I just need to get over the hump and get both sides working well enough,” Bratcher said. “I hate not being able to do the things that I love, that’s what’s most frustrating. The only thing that’s really going to help my left arm is rest.”

Resting his left arm is dependent upon acquiring a more efficient prosthesis.

A possible solution arose last summer when a group of engineering students at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo expressed an interest in making Bratcher a custom prosthetic called a myoelectric hand. The project has gained traction after an initial meeting on Feb. 4.

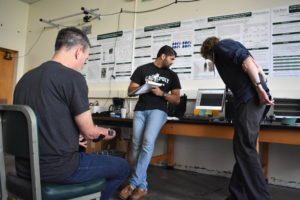

Cal Poly’s Quality of Life Plus (QL+) Student Association develops innovative medical devices by harnessing the creativity and skills of engineering students.

“We saw an article about him struggling to get the prosthesis he wanted and we reached out to the author of the article, who put us in touch with Dr. Bratcher,” said Johnathan Dewing, senior vice president of QL+. “Our goal is to create an electrically powered prosthetic hand that will serve Dr. Bratcher better than his current prosthesis.”

In contrast to conventional prosthetics, myoelectric technology offers superior precision in movement and a more intuitive user experience. The artificial limb is controlled with sensitive electrodes that respond to the natural movements of muscles.

Bratcher first met with his design team — seven engineering students with mechanical, electrical, biomedical, and programming backgrounds — in the QL+ lab at Cal Poly. Together they determined which features were most important to the tasks Bratcher needs to perform: driving a stick shift, lifting 35-pound wine cases, typing, leveraging, holding, and greeting someone with a handshake.

“To me, it’s more about function over form. I don’t care much for how it looks, it just needs to be able to do what I need it to do,” Bratcher said.

The students performed an electromyogram (EMG) test to determine which of Bratcher’s forearm muscles would provide the best feedback to the prosthesis. Several hours later the team had made impressions of his left arm and taken precise measurements of his left hand.

Several weeks after the first meeting, the team has moved into building the socket, ordering electronic components, and printing parts for the palm and digit with a 3D printer. They expect to have a prototype by the end of the academic quarter in late March.

“We are gradually putting together the hand. So far the electronics and programming is the slowest process, as we are finding it challenging to source components like sensors, but we are constantly working to clear these hurdles,” wrote team leader Aaliyah Ramos in an update.

Bratcher is eager to see the results of the design team’s efforts, but his hopes are balanced by reasonable expectations. Perhaps the final product will enable him to finally enjoy a round of golf again and go rock climbing at the crag near his other home in Chattanooga, Tenn. Or perhaps not. Either way, he’s not one to wallow in the sentiment of loss.

“I’ll be as patient as I have to be, and as persistent as I need to be. I don’t sit around thinking to myself, ‘Oh man, that was so great when I had two hands.’ I just don’t have time for that, I really don’t,” Bratcher reflected. “For better or for worse, I’m always looking forwards. It’s just a part of my personality. I don’t dwell on the past, at all. That, probably more than anything else, has been my saving grace.”

Keep reading the Santa Ynez Valley Star for further updates on Chris Bratcher’s journey. You can learn more about the QL+ club at qlplus.calpoly.edu.